For years I’d read about radio meteor scatter – the idea that you can detect meteors you can’t see by listening to radio reflections in the upper atmosphere. Over the Christmas period I decided to stop reading and actually try it, using inexpensive hardware and open-source tools.

This post documents what I did, what worked, what didn’t, and crucially, how I checked whether the results were real.

What is radio meteor scatter?

When a meteor enters the Earth’s atmosphere it ionises a thin trail of air, typically at altitudes of 80–120 km. For a fraction of a second (sometimes longer), that ionised trail can reflect radio signals.

If you monitor a continuous, distant radio transmitter, those reflections appear as brief spikes in signal strength. You never hear or see the meteor directly, you detect its radio footprint.

Radio meteor scatter is used professionally and by amateur networks across Europe and North America.

My setup

This was deliberately modest.

Hardware

- RTL-SDR Blog V4 dongle

- Simple VHF antenna

Software

rtl_power(from thertl-sdrtoolkit)- macOS

- Spreadsheet + Python for analysis

Target frequency

- 143.05 MHz – reflections from the French GRAVES space-surveillance radar, a standard choice for European meteor scatter work

The recording method

Rather than watching a live waterfall display, I used unattended signal-strength logging, which is the correct approach for overnight meteor work.

The command used:

rtl_power -f 143050000:143050001:1 -i 1 -e 8h meteors.csv

This:

- Monitors a single frequency bin at 143.05 MHz

- Records one power measurement per second

- Runs unattended for several hours

- Produces a CSV file for later analysis

During recording:

- All other SDR software was closed

- The computer was prevented from sleeping

- No manual intervention was required

What the raw data looks like

Most of the time, the signal sits at a fairly stable baseline.

Meteor reflections appear as sudden, short-lived increases in signal strength — typically lasting one or two samples.

This is exactly what theory predicts.

Detecting meteors in the data

To avoid fooling myself, I used a conservative detection threshold:

- Calculate the mean signal level

- Flag a meteor only when the signal exceeded the mean by +5 dB

This is intentionally strict. It reduces false positives at the expense of missing some very weak events.

Using that method, the dataset contained:

- 58 distinct meteor-scatter events

- Over roughly 28 minutes of data

- Equivalent to ~2 events per minute

These were overwhelmingly short, impulsive reflections — consistent with sporadic background meteors, not a major shower.

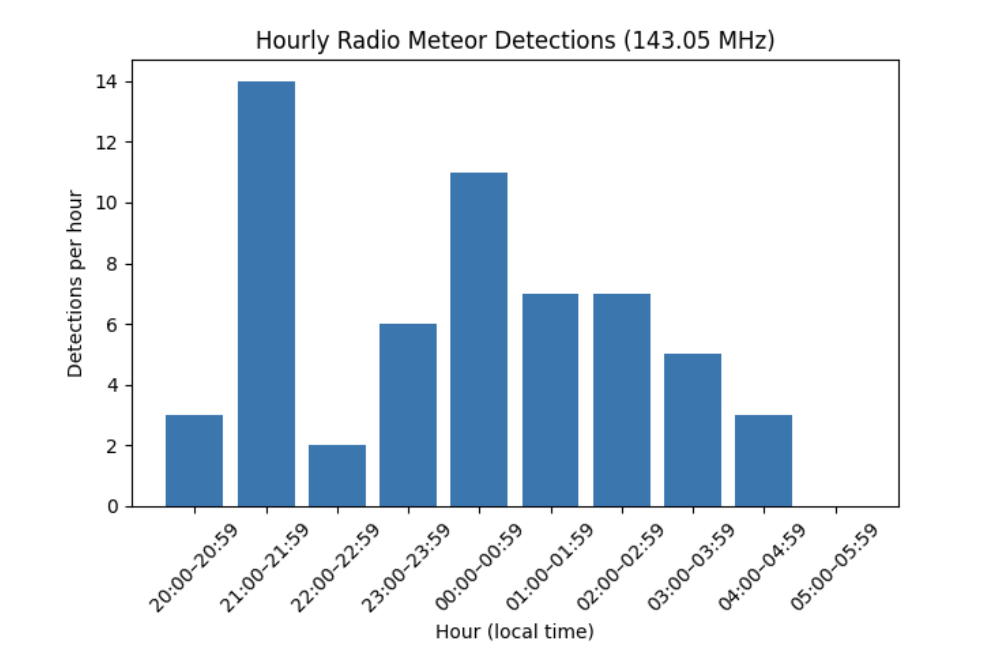

Turning detections into a comparison chart

To compare my results with professional networks, I binned detections into hourly counts, producing this table:

| Hour | Meteors |

|---|---|

| 20–21 | 3 |

| 21–22 | 14 |

| 22–23 | 2 |

| 23–00 | 6 |

| 00–01 | 11 |

| 01–02 | 7 |

| 02–03 | 7 |

| 03–04 | 5 |

| 04–05 | 3 |

This is important, because professional networks do not compare absolute counts between stations — they compare activity trends over time.

My hourly results showed:

- Low activity early in the evening

- Sustained activity after midnight

- A gradual decline toward morning

- No sharp peak (as expected outside a major shower)

In other words: a textbook sporadic-meteor count.

Why direct comparison with professional networks is difficult

At this point, it would be tempting to directly compare these hourly counts with those from professional radio meteor networks such as the Belgian Radio Meteor Stations (BRAMS). In practice, this turns out to be difficult for several reasons.

BRAMS publicly provides:

-

Network data availability plots, showing when stations were operational

-

Research papers and processed results

What it does not provide openly:

-

Simple, per-night, per-hour public meteor count tables

-

Raw station-level detection counts suitable for direct numerical comparison

This is not an oversight. BRAMS detections are subject to calibration, filtering, and classification before being used in scientific outputs. Absolute meteor counts depend strongly on antenna characteristics, receiver sensitivity, geometry, and detection thresholds — all of which differ from a single-station RTL-SDR setup.

As a result, professional practice does not rely on matching raw hourly counts between systems. Instead, comparisons are normally qualitative, focusing on:

-

Whether activity is generally low or high

-

Whether rates increase after midnight

-

Whether known meteor showers produce clear increases

Attempting a one-to-one numerical comparison would therefore be misleading.

What can still be concluded

Even without direct comparison to professional hourly counts, the experiment demonstrates that:

-

An inexpensive RTL-SDR can detect genuine meteor scatter events

-

Unattended signal-strength logging is an effective approach

-

The detected events match the expected physical behaviour of meteor reflections

-

Hourly counts show the expected variation for sporadic background meteors

The limitations encountered are not a failure of the experiment, but a reflection of how validation in radio meteor work is normally performed: by comparing temporal behaviour, not absolute numbers.

Next steps

Future work could include:

-

Longer pre-dawn observing runs, when meteor rates are highest

-

Collecting multiple nights of hourly count tables to examine repeatability

-

Observing during a major shower to look for a clear increase in hourly counts

-

Comparing results qualitatively with published professional activity summaries

As a first experiment, this project achieved its main aim:

detecting real meteors using radio alone, with transparent methods and a clear understanding of the limits of comparison.

What this experiment does not show

- It does not identify individual meteors

- It does not match professional radar sensitivity

- It does not replace optical observations

- It does not measure meteor orbits or speeds

Those would require more sophisticated setups and multi-station analysis.

Next steps

Possible next steps include:

- Running pre-dawn sessions (when rates are highest)

- Comparing multiple nights to detect shower activity

- Refining thresholds to distinguish short vs long echoes

- Normalising activity curves for long-term monitoring

But as a first experiment, this achieved its main goal:

independently detecting real meteors using radio alone — and proving it.

If you’re interested in SDR, radio science, or data-driven experimentation, this is one of the most rewarding projects you can try with very little equipment.