During the Christmas break, I set up a small radio experiment with a simple goal: could a low-cost software-defined radio detect the rise and fall of a real meteor shower?

Between 29 December 2025 and 9 January 2026, I ran an RTL-SDR dongle continuously to monitor a distant VHF radio transmitter. By recording short bursts of reflected signal caused by meteor ionisation trails in the upper atmosphere, I aimed to capture the activity of the Quadrantid meteor shower using radio scatter detection.

The experiment worked remarkably well.

Radio detection of meteors

When a meteoroid enters Earth’s atmosphere, it creates a brief trail of ionised gas at altitudes around 90–110 km. These trails can reflect VHF radio signals for fractions of a second. If a receiver is monitoring a distant transmitter beyond the normal radio horizon, these reflections appear as short-lived bursts of signal.

This method, radio scatter meteor detection, allows meteor activity to be measured regardless of cloud cover or daylight, making it ideal for winter observing.

The Quadrantids

The Quadrantid meteor shower is active from late December to early January, with a sharply defined peak usually occurring around 3–4 January. Visual zenithal hourly rates during the peak can exceed 100 meteors per hour, but the intense maximum lasts only a few hours, making it a good test of whether a radio system can detect a genuine, time-limited astronomical event rather than background noise.

Experimental setup

The equipment was intentionally simple:

- RTL-SDR USB receiver

- Basic VHF antenna

- Laptop running SDR software

- A distant VHF transmitter used as a reference signal

Signal strength was logged continuously to CSV files, producing timestamped measurements throughout the experiment. Short-duration signal bursts are consistent with reflections from meteor ionisation trails, though occasional interference from other sources is also possible. Over long time periods, however, the rate of such bursts provides a reliable measure of relative meteor activity.

Data preparation

Recording sessions did not all start and end at the same time. One day (1 January) was split across two files, which were merged into a single continuous dataset before analysis.

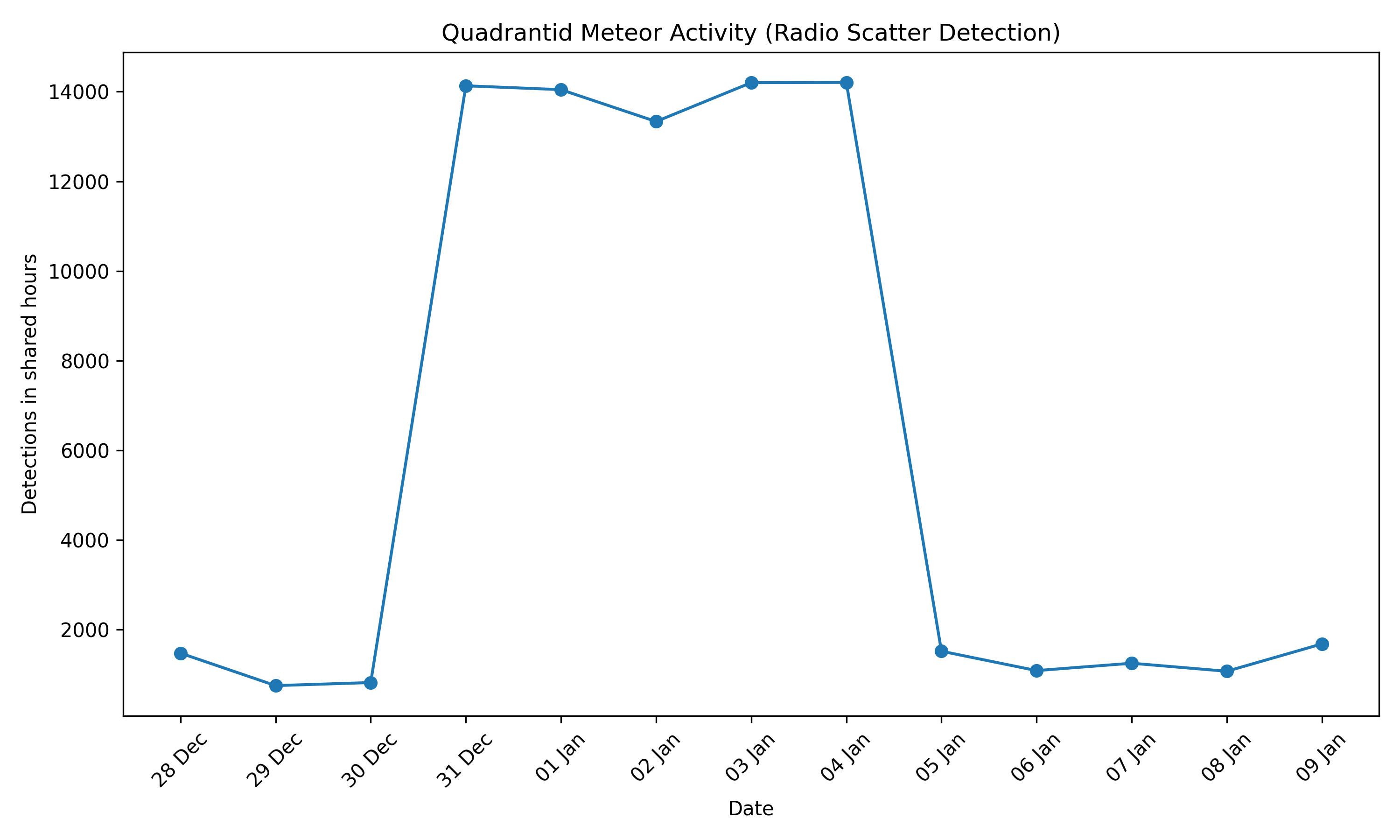

To ensure fair comparison between days, I identified which hours of the day were present in every dataset. After merging the split files, eight shared hours were common to all recordings: 21:00 to 04:00.

To avoid bias from missing coverage, only data from these shared hours were used when comparing daily detection rates. This produced a consistent, like-for-like dataset across the full experiment.

Results

Using only the shared hours, I calculated the total number of detected signal bursts per day. The resulting detection-rate curve shows:

- Low background activity in late December

- Rising activity in early January

- A pronounced peak on 3–4 January

- A rapid decline thereafter

The timing of this peak is consistent with published predictions for the Quadrantid meteor shower. This indicates that the radio system successfully captured the shower’s activity pattern.

Daily detection counts (shared recorded hours only)

| Date | Detections |

|---|---|

| 28 December 2025 | 1478 |

| 29 December 2025 | 754 |

| 30 December 2025 | 822 |

| 31 December 2025 | 14131 |

| 1 January 2026 | 14045 |

| 2 January 2026 | 13334 |

| 3 January 2026 | 14201 |

| 4 January 2026 | 14206 |

| 5 January 2026 | 1521 |

| 6 January 2026 | 1089 |

| 7 January 2026 | 1253 |

| 8 January 2026 | 1074 |

| 9 January 2026 | 1684 |

Reflections

Several aspects of the experiment stood out:

- The large number of detectable events compared with visual observing

- The stability of the system once configured correctly

- How accessible radio-based meteor detection has become with modern SDR hardware

Although refinements are possible — such as automated burst classification or multi-frequency comparisons — the core objective was met: a small, low-cost radio setup recorded the characteristic activity profile of a major meteor shower.

Closing thoughts

The Quadrantids passed unseen above winter cloud, but their presence was recorded clearly in radio data. It is satisfying to see that modest equipment, careful logging, and simple analysis can reveal real astronomical phenomena.

Not bad for a holiday experiment.